Bravo!

Now you have found the treasure, find out more about the artworks

Figures and legends

A

Taddeo Gaddi frescoed the Tree of Life and the Last Supper in the refectory, where the Franciscan friars used to take their meals together, between 1345 and 1350. You’ll notice that the crucifix is shown at the heart of a very complex composition celebrating Jesus’s sacrifice, which led to the salvation of mankind.

B

Giovanni Lami’s monumental tomb, carved by Innocenzo Spinazzi between 1772 and 1775, is in the basilica’s north aisle. Lami was famous for his work as a historian and librarian, and the bronze animals on his tomb are meant to symbolise his talents. Unfortunately, the sculptor did not leave any written instructions to help us interpret his work, but it’s highly likely that the dolphin symbolises a quick mind, the dove a peaceful temperament, and the owl wisdom.

C

Bernardo Rossellino carved the Monumental tomb of Leonardo Bruni, a chancellor of the Florentine Republic, between 1445 and 1450. The tomb stands in the basilica’s south aisle. This was the work of art that set the standard for monumental tombs typical of the Florentine Renaissance, i.e. tombs usually set vertically against the wall of a church. The overall effect is often pretty impressive because the aim was to honour the memory of illustrious figures, whose qualities and talents are illustrated with inscriptions and decorations.

D

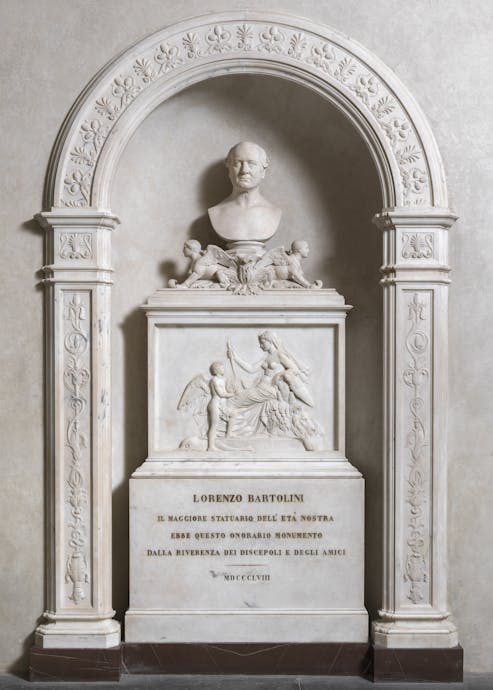

Lorenzo Bartolini’s Memorial, carved by Pasquale Romanelli and Tommaso Gasperini in 1858, stands in the corridor leading to the Novitiate. Bartolini was a great Italian sculptor and he carved a lot of the statues in Santa Croce. His importance is mentioned in his epitaph (i.e. the words engraved on his tomb), which also tells us that the tomb was commissioned by Bartolini’s pupils and friends who were eager to keep his memory alive… It may come as no surprise that Romanelli and Gasperini were two of his pupils!

E

Dante Alighieri’s Cenotaph, carved by Stefano Ricci between 1818 and 1829, is in the basilica’s south aisle. Dante, who died in 1321, was already considered one of Italy’s greatest poets in the 19th century. In fact, he was known as the “father of the Italian language”. Because Ricci couldn’t carve a portrait of Dante from life, he chose to illustrate his greatness by making him look like an ancient hero both physically and in his clothing. He also added a few small details traditionally associated with Dante such as his aquiline nose, his typical headgear and a laurel wreath symbolising poetry. It’s what’s known as an “idealised” portrait.

F

Stanislao Bechi’s commemorative plaque, carved byTeofil Lenartowicz in 1882, is in the first cloister. The plaque celebrates the memory of Stanislao Bechi, who died fighting for Poland’s independence. The relief shows him in front of the firing squad, refusing the blindfold that would have covered his eyes. Facing death with your eyes open was considered an extremely brave gesture.